Javascript tools for end-to-end testing web applications

Earlier, I compared1 a few different tools for unit testing Javascript code. This post reviews available tools for end-to-end testing web applications using Javascript (i.e. tests that click buttons, type text etc). Many UI frameworks comes with a tool for this, but I’m looking specifically for a framework neutral tool so I’m not considering for example Protractor (Angular), Capybara (Ruby on Rails), Mirage (Ember) etc.

I want my E2E tests to:

- smoke test all layers of the application running together (frontend/backend)

- catch browser specific issues (even though browser bugs per se are getting increasingly rare, you typically need to verify that your polyfills are complete and working in each browser for example)

- click through parts of the application that are not current being changed/developed to guard against regressions when shared components changes

- always report any JS exceptions (if I have assertions verifying correctness for the most important part of a page/screen, I still want a systematic check that no JS exceptions happened for example when some less important “below the fold” part of the page loaded. I don’t want full coverage with assertions in E2E tests, I prefer to push as much as possible to component level tests)

Why should you implement E2E tests in Javascript?

A web application end-to-end testcase will send commands to a real browser and wait for it to complete before sending the next command. Commands are often (but not always) sent to the browser via Selenium or at least the Webdriver API. This means that the testcases are, by their nature, a long string of asynchronous operations. Given the “sort of single-thread” nature of Javascript, there is a potential for “callback hell” issues. Java on the other hand can execute many testcases in parallel using OS threads and block for each asynchronous operation, thus providing a very easy to use API. On top of that Selenium itself is written in Java, so it’s fair to ask why not just write E2E tests in Java?

If your backend is not JVM-based (e.g. Node/Python/golang/PHP), it’s inconvenient to force all

developers to install a JRE/JDK, IDEA or Maven/Gradle solely for E2E tests (if you target the

webdriver binary directly, you don’t even need a JRE installed, although some cloud testing

providers still require you to go via a Selenium server). Even if you have a JVM-based backend

already, it’s much faster to iterate on E2E tests written in Javascript (you certainly don’t want to

wait for a slow Maven multi-module reactor build) and your testcases doesn’t need HotSpot JIT

anyway. On top of that, if your E2E tests execute in Node rather than in a browser, it’s possible to

use coroutines implemented by the node-fibers package to create a API that looks and feels

synchronous. This allows you to put breakpoints half way into your testcase etc, which is a bit

trickier with APIs with chained asynchronous

methods (which

is also used quite frequently among E2E test frameworks implemented in Javascript).

What are the available options/tools for UI automation in JS?

Among the tools/frameworks that comes up when you google for “end to end testing”, I immediately ruled out a few, like PhantomJS/CasperJS (not a real browser, about to be replaced by headless Chrome anyway). Zombie.js does not test in a real browser and while impressive it looks a lot like a one man project that went into maintenance mode. However, Zombie.js is based on a really good idea (getting rid of slowness and flakiness by targetting jsdom). It would be nice if this approach was combined with full browser testing so that the testcases first ran really fast using jsdom (to make it quick to iterate and develop new testcases) and once they passed there, all testcases would run again but inside all the target browsers. This was attempted in taxi-rank, which is based on cabbie. However, there wasn’t a lot of good articles/examples/documentation about these and NPM downloads are super low so I didn’t spend any time on them, but I like the idea.

Another really nice project is NightmareJS that runs UI automation inside Electron (so it’s much closer to Chromium compared to PhantomJS). It’s much faster than Selenium and avoids a lot of the messy configuration and flakiness that comes with trying to launch a real browser. I’ve used it for a lot of things, but for the purposes of this comparison I’m not including it since it cannot run testcases inside a real browser (and I explicitly want to test in Firefox etc). Dalek.js can test in a browser but the project was never finished and is not maintained anymore. Buster.js and TotoroJS were also abandoned/unmaintained and didn’t pass a 5 second sniff test.

I saw a few people tweeting about Cypress.io so I included it although it’s in closed beta (not technically open source right now but they claim that will change fairly soon).

Which E2E tools/frameworks were compared?

The full list of tools that I ended up trying out was:

| License | API style | Issue Latency 2 | Open / All Issues 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| selenium-webdriver | Apache-2.0 | fake sync or async/await | n/a | n/a |

| wd.js | Apache-2.0 | multiple | 1 day | 7% |

| Nightwatch.js | MIT | async chain | 1 days | 12% |

| Webdriver.io | MIT | coroutine sync | 12 hours | 4% |

| Chimp | MIT | coroutine sync | 75 days | 19% |

| Nemo | Apache-2.0 | fake sync | 10 days | 16% |

| CodeceptJS | MIT | coroutine sync | 30 days | 19% |

| Intern | New BSD | async chained | 26 days | 10% |

| TestCafe | MIT | await single chain | 7 days | 16% |

| Cypress | ? | async chained | 49 days | 32% |

Don’t read to much into the issue latency numbers without checking the issues yourself, for example I opened a bug with Cypress recently and they triaged it and assigned it to a developer the same day and it was fixed 24 hours later.

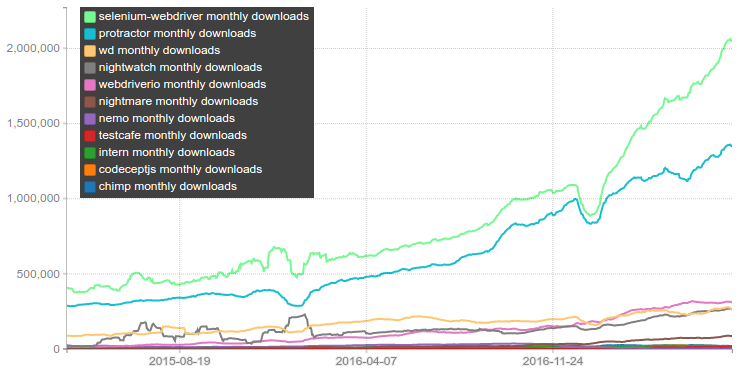

If you render the monthly downloads for each of these NPM packages (and protractor as well for reference), you get this plot:

The protractor package depends on selenium-webdriver, so that drives selenium-webdriver downloads quite a bit. In general, NPM download statistics should be taken with a grain of salt due to mirrors and download bots, downloads by CI systems and cached installs. And you cannot tell if a package has high download numbers because IT is popular or if it’s because it has a popular package depending on it. Note that nemo.js depends on selenium-webdriver, Chimp depends on WebdriverIO and CodeceptJS depends on protractor, webdriverio and selenium-webdriver (it can execute using multiple backends).

If we zoom into the weeds, we see that during 2017 alone CodeceptJS and TestCafe both enjoyed >100% increase in downloads whereas Chimp and Intern are largely constant. Just for fun, I also included “nightmare” in the chart, it certainly has been gaining a lot popularity during 2017 (currently at 4x of where it was in october last year).

Another interesting thing is the sharp drop in downloads for nemo; but this is partly due to Paypal setting up an internal NPM mirror (they still use nemo).

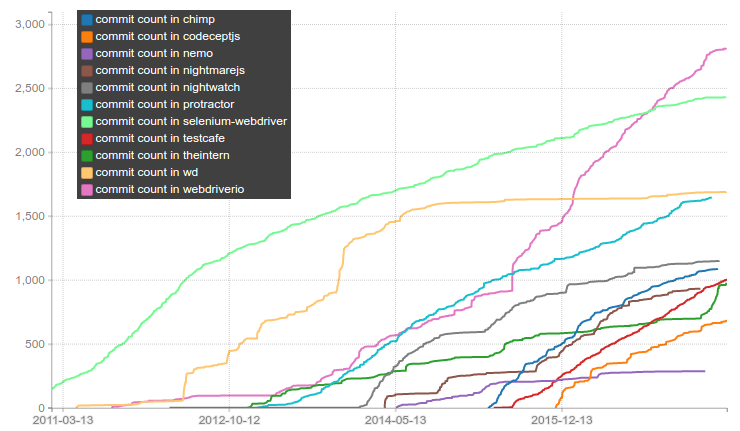

Another interesting thing to look at is the number of commits in the git repository for each of these test tools. Cypress isn’t open source yet so I couldn’t include it. selenium-webdriver lives in the main selenium repository inside a directory called “javascript” so I did a quick git filter-branch on that directory and measured only commits that touched that directory.

Anyway, if you plot the commit count over time you get this:

The git data goes back a lot longer than the NPM downloads data, maybe wd.js had more NPM downloads during the period when it also had a lot of commits landing. A lot of work was done on wd.js from 2012 to 2014 (FWIW; the main author of wd.js is Adam Christian, who worked for Sauce Labs 2010 to 2015). Webdriver.io started to pick up speed in 2013, and unlike wd.js, is still going strong. It’s headed by Christian Bromann (who works for, you guessed it, Sauce Labs).

Another notable thing in the commit count chart above, is the steep increase for Intern starting in April; this is Jason Cheatham kicking off development of Intern v4 (more on that later).

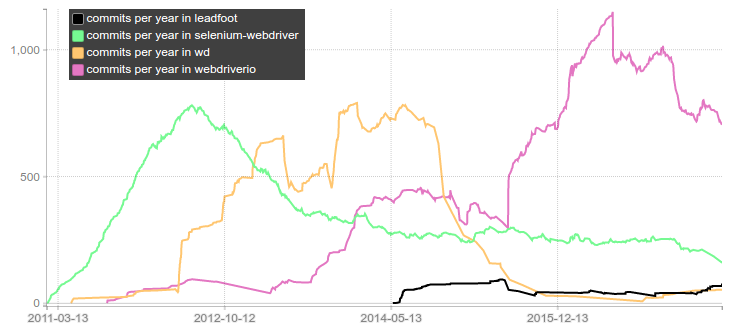

Below is another plot of the same data; showing commits per year for the three major webdriver implementations and I’ve also added in leadfoot which is an independent webdriver implementation used by Intern (they used wd.js in v1 before developing leadfoot):

Another great way to estimate how many people are invested in a certain technology is to analyze how the number of active developers changes over time. To visualize this, I’ve plotted the number of unique developers seen in the git log during a rolling 365 day window:

This shows strong community momentum for webdriver.io and to some extent CodeceptJS.

I also tried to write a few testcases using each framework. I created a small test page that had a

button which started a timer and then eventually made a div visible with some text, and also some

other easy scenarios. The test page could also be configured to be buggy, and then various bad

things would happen like the element not being added to DOM, some JS error would occur even though

the page appeared otherwise to be working, or the element was added to the DOM but inside another

div that had overflow:hidden and the child div was then placed outside of the cliprect of the parent

making it invisible while still not having display: none. I wanted to see how each framework

responded to these “bugs” and how easy it was to understand the error messages / test results etc.

Below are some code examples (in reality you should of course not be hardcoding selectors like this, but instead use the page object pattern or something similar). I’ve also included a few notes for each framework.

selenium-webdriver

For selenium-webdriver, I used regular MochaJS as the runner. I disabled the global promise manager that is used to provide the older “fake sync” API, and I used async/await instead (without transpilation! Yay, Node v8!). The testcases looked sort of like this:

it('scenario 3', async function() {

await driver.get('file://' + path.join(__dirname, '../../test-pages/index.html'));

await driver.findElement(By.xpath('//*[text()="button3"]')).click();

const element = until.elementIsVisible(driver.findElement(By.id('hidden3')));

const actualElement = await driver.wait(element, ELEMENT_TIMEOUT);

assert.equal(await actualElement.getText(), 'hidden3 pass');

});

The .get() call blocks until the page has loaded fully so normally you can just do for example

driver.findElement(By.name('q')).sendKeys('webdriver') but #hidden3 above was added by a

timer after the button was pressed so I needed to add the explicit wait.

Selenium and WebDriver in general doesn’t have protocol support for streaming JS errors via the driver, which is a shame because it would be so useful! However, there is support in the protocol for retrieving the JS console log at least, so I was able to assert that there were no JS errors, by using this clunky hack:

it('scenario 2', async function() {

await driver.get('file://' + path.join(__dirname, '../../test-pages/index.html'));

await driver.findElement(By.css('.button2')).click();

const hidden2 = until.elementIsVisible(driver.findElement(By.id('hidden2')));

const hidden2actual = await driver.wait(hidden2, ELEMENT_TIMEOUT);

assert.equal(await hidden2actual.getText(), 'hidden2 pass');

const browserLog = await driver.manage().logs().get(logging.Type.BROWSER);

const errors = browserLog.filter(entry => entry.level.name === 'SEVERE')

errors.forEach(entry => console.log('[%s] %s', entry.level.name, entry.message))

assert.ok(errors.length == 0, 'JS errors in browser log!');

});

If you’re going to use selenium-webdriver, then you should be using this modern async/await API that I showed above, but there is also an older “fake sync” API that looked like this:

driver.get('http://www.google.com/ncr');

driver.findElement(By.name('q')).sendKeys('webdriver');

driver.findElement(By.name('btnG')).click();

driver.wait(until.titleIs('webdriver - Google Search'), 1000);

driver.quit();

console.log('all done');

This looks synchronous but it is not, instead each of the methods will append their action to a

chain of promises that won’t even start until the next runslice. This means that the code will first

print “all done” and then it will begin the navigation to google.com. It also means that you cannot

stop the testcase halfway through by inserting debugger between two lines. You can call it

from inside a then, chained after another line, like this:

...

driver.get('http://www.google.com/ncr').then(() => {debugger});

...

In general, my impression of selenium-webdriver was quite bad because not even the “hello world” example would run due to #4041 and while this fix bug was fixed by Lucas Tierney (kudos!) unfortunately no new release has been pushed to NPM for this critical bug (it’s been >2 months now).

Another drawback for “selenium-webdriver” is the generic name it has. It’s very hard to google for examples and help for this tool because you keep hitting articles about selenium webdriver in C#, Java, Ruby etc etc. This was actually surprisingly frustrating.

wd.js

wd.js offers multiple APIs; one pure async API for those who are really into indentation, one non-chained API based on Q promises for people who enjoy writing .then() a lot, one based on generators and of course one API based on chained async calls (also using Q promises). Their readme doesn’t mention any examples using async/await, though it’s probably not hard to setup if you want it. I thought it was quite interesting to look at all of these API examples in their readme.

Code using the chained Q API looks like this:

browser

.init({browserName:'chrome'})

.get("http://admc.io/wd/test-pages/guinea-pig.html")

.title()

.should.become('WD Tests')

.elementById('i am a link')

.click()

.eval("window.location.href")

.should.eventually.include('guinea-pig2')

.back()

.elementByCss('#comments').type('Bonjour!')

.getValue().should.become('Bonjour!')

.fin(function() {

return browser.quit();

})

.done();

The commits per year plot earlier suggests that webdriverio has much stronger momentum compared to wd.js so I didn’t bother to write my own testcase for wd.

nightwatch.js

Nightwatch offers a async chained API and runs on top of a built-in (forked) mocha version. A test could look like this:

this.scenario3 = function (browser) {

browser

.url('file://' + path.join(__dirname, '../../../test-pages/index.html'))

.useXpath()

.click('//*[text()="button3"]')

.useCss()

.waitForElementVisible('#hidden3', ELEMENT_TIMEOUT)

.assert.containsText('#hidden3', 'hidden3 pass')

.end();

};

The chain executes asynchronously so you can’t break it apart and put debugger in the middle,

instead you have to inject your code into the chain; by using for example: .perform(() =>

{debugger}).

You can run tests using nightwatch -c nightwatch.json and use --env chrome if you want

to run tests in chrome instead of Firefox etc. In the config file you can set the paths to your

geckodriver and to the selenium server jar, and then just set selenium.start_process to true.

I also wanted all testcases to finish even if the first one failed so I set

skip_testcases_on_fail to false. I was able to retrieve the JS log using the same clunky way I

used for selenium-webdriver. The config, command line output and command line switches all just

works the way you’d expect them to.

I didn’t try it, but it seems possible to run your nightwatch tests via Sauce Labs quite easily. There is also another cloud testing service called nightcloud.io being developed.

In general, Nightwatch feels like a very competent tool. The only drawback I can think of is that it seems that nightwatch was largely written by a single guy, so it has a low bus factor.

webdriver.io

If you disgard selenium-webdriver downloads (and protractor drives a lot of those), Webdriver.io is the most downloaded E2E package on NPM. Webdriver.io is also the framework with the most active developers working on it, in the last year alone over 130 different developers sent at least one patch to this project.

The code looks like this:

it('scenario 3', () => {

browser.url('https://www.whatever.com/something/');

browser.click('//*[text()="button3"]');

browser.waitForVisible('#hidden3', ELEMENT_TIMEOUT)

assert.strictEqual(browser.getText('#hidden3'), 'hidden3 pass');

});

This code looks superficially similar to the “fake sync” API of selenium-webdriver, but it is

really not the same. If you drop execArgv: ['--inspect-brk'], into your wdio.conf.js and

then add debugger somewhere in the middle of the testcase, like this:

it('scenario 3', () => {

browser.url('https://www.whatever.com/something/');

browser.click('//*[text()="button3"]');

debugger

browser.waitForVisible('#hidden3', ELEMENT_TIMEOUT)

assert.strictEqual(browser.getText('#hidden3'), 'hidden3 pass');

});

..then the debugger will actually execute the first part of the testcase, open the URL, wait for it

to finish loading and then click the button. Only after those things are finished executing will it

hit the debugger breakpoint. This is possible because webdriverio uses proper coroutines

implemented in native code and supplied by the node-fibers package. This means that for

example the, .url() method can send a message to the browser saying that it should navigate to

a particular url and then execution context suspends itself in such a way that it’s not resumed

until the browser has finished loading the URL. From the outside, it appears like .url() is

synchronous even though node is still “single threaded” and we havn’t used any additional OS

threads.

Another neat feature for webdriverio is that it has a really good REPL that fires up a browser and

then you can experiment with commands and selectors from there. Even better, you can insert

browser.debug(); into an existing testcase and have it drop into a REPL at that particular

place in the testcase.

The current getting started documentation on the webdriver.io site

is not ideal imo. It has lots of steps in the beginning asking you to download specific versions of

the selenium server jar, geckodriver, chromedriver etc which is both fiddly and error prone. A bit

later on in the guide it mentions wdio, and much later I learned about

wdio-selenium-standalone-service which automatically sets everything up. Also, at first I couldn’t

find a way to override the configured browser from the command line, but then I realized I could set

the config to browserName: process.env.SELENIUM_BROWSER || 'firefox' and override it with an

environment variable. The config can also list multiple browsers if you want to test locally in

Chrome and Firefox simultaneously, e.g. put this at the end of your wdio.conf.js:

if (process.env.SELENIUM_BROWSER) {

exports.config.capabilities = [{

browserName: process.env.SELENIUM_BROWSER

}];

} else {

exports.config.capabilities = [

{

browserName: 'chrome'

},

{

browserName: 'firefox'

}

];

}

I also ended up setting timeout: 30000 inside mochaOpts. Running with --logLevel

verbose was useful for debugging. The watch mode is also very useful.

To assert that no JS errors were encountered, I had to explicitly download the browser log in the end of the testcase, just like I did for selenium-webdriver. Sad!

chimp

chimp is a framework built on top of webdriver.io, an example testcase looks like this:

browser.url('https://www.whatever.com/something/');

browser.click('//*[text()="button3"]');

browser.waitForVisible('#hidden3', ELEMENT_TIMEOUT)

assert.strictEqual(browser.getText('#hidden3'), 'hidden3 pass');

There was a few things I didn’t like about chimp. It talks a lot about Meteor/DDP and Also, chimp

--help doesn’t print anything and for every test run it prints “Master Chimp and become a testing

Ninja! Check out our course: http://…”

In the end I didn’t think chimp added enough on top of webdriver.io to make it worth the additional dependency.

nemo.js

This E2E framework was developed by PayPal. An example testcase looks like this:

/*global describe:true, it:true */

var basedir = require('path').resolve(__dirname, '..');

var Nemo = require('nemo');

var nemo;

describe('suite using @generic@ nemo-view methods', function () {

before(function (done) {

nemo = Nemo(basedir, function (err) {

if (err) {

return done(err);

}

done();

});

});

after(function (done) {

nemo.driver.quit().then(done);

});

it('should automate the browser', function (done) {

//login

nemo.driver.get(nemo.data.baseUrl);

nemo.view._waitVisible('id:signup-button').click();

nemo.view._waitVisible('id:cta-btn').click();

nemo.view._waitVisible('id:email').sendKeys('mynewpaypalaccount@geemail.paypal');

nemo.driver.sleep(3000).then(function () {

done();

}, function (err) {

done(err);

})

});

});

Nemo starts up with selenium-webdriver 2.53.3 which is incompatible with Firefox v48 and all later versions of Firefox (i.e. all versions of Firefox released since mid-2016). Their homepage mentions this and says users should downgrade Firefox or upgrade to a new major version of selenium-webdriver that hasn’t been tested with nemo. It also prints a few other east to fix deprecation warnings like os.tmpDir vs os.tmpdir etc.

CodeceptJS

This framework allows you to run your testcases on top of either webdriverIO, selenium-webdriver, protractor or NightmareJS. Their API uses generators to deal with the asynchronicity:

Feature('Test1.js');

Scenario('test something', function*(I) {

I.amOnPage('/');

I.fillField('[name=q]', 'hello world')

I.waitForElement("h3.r", 30)

I.see('"Hello, World!" program - Wikipedia');

const titles = yield I.grabTextFrom('h3.r')

console.log(titles.join("\n"));

});

When I first tried to install the codeceptjs-webdriverio package it failed to install

properly, so I filed issue #1 (yay!)

and 25 days later a fix was pushed.

From what I can tell, CodeceptJS doesn’t even have an API to fetch the browser JS log, so I could not implement a check that verifies that no JS error happened on the page.

TestCafe

TestCafe is developed by a company called DevExpress who open sourced it in October 2016. They continue to work on it quite intensely (they are landing about 480 commits per year which is higher than all other frameworks except for webdriverio at >700 commits per year). The most interesting thing about this framework is that it does NOT use selenium or webdriver at all. Instead parts of the test framework itself executes inside the browser.

A typical testcase looks like this:

fixture `example page`

.page `${testpageUrl}`;

test('scenario 1', async t => {

await t

.click('#button1')

.expect(Selector('#hidden1').innerText).eql('hidden1 pass')

});

If you’re not familar with the syntax near “fixture”; it’s an ES6 tagged template literal.

One really awesome thing about testcafe is that it automatically detects JS errors that happened when the test page was executing. I suppose this is the kind of awesome you can attain when you reach outside of the Selenium box! I also noted that the terminal output when tests failed where quite readable/clean.

TestCafe doesn’t support XPath selectors

(#1178) but it has a special API for locating

elements by text: Selector('form input').withText('Submit').

Intern

Next up is Intern; a typical testcase looks like this:

'login works'() {

return this.remote

.get('index.html')

.findById('username')

.type('scroob')

.end()

.findById('password')

.type('12345')

.end()

.findById('login')

.click()

.end()

.sleep(5000)

.findByTagName('h1')

.getVisibleText()

.then(text => {

assert.equal(text, 'Welcome!');

});

}

As mentioned in conjunction with the “commit count over time” plot earlier, Jason Cheatham is currently working on Intern v4 (the example above is from v4). There are only alpha releases available so far, but the idea is that the final release will be “mostly API compatible” with the latest alpha. Intern v4 will be used to test the new version of the Dojo framework.

While earlier versions required you to declare your test suites as AMD modules, now with Intern v4 you can just babel-register and use require (and the built-in code coverage works even for transpiled code!). Under the hood, Intern itself has been rewritten in TypeScript.

My impression of Intern is that it’s by far the most difficult framework to setup, this will probably change once v4 is finished though (both in terms of reduced quirks and better documentation).

Cypress

This framework is currently in closed beta. Luckily I was able to get an early invite (thanks Jennifer!). Cypress runs via Mocha and its API uses async chaining:

it('scenario 2', () => {

cy

.visit(testpageUrl)

.get('.button2')

.click()

.get('#hidden2')

.should('be.visible')

.should('have.text', 'hidden2 pass')

});

It does not use selenium or webdriver, instead parts of the test framework is injected into the

browser directly. If the test runner needs to do privileged actions like read a file from disk, it

makes a request to a local webserver that performs the action for it (or in some cases a browser

extension is used as well). For alert popups, Cypress currently auto accepts them but that

doesn’t work if they are coming from an iframe

(#376).

Cypress also comes with the ability to optionally intercept XHR requests from the browser to immediately return a static result, speeding up testcases where such a trade-off is appropriate. It comes with bundled versions of chai, sinon, moment, lodash and jQuery. The documentation is really good. Finally, Cypress ships with a GUI application based on Electron where you can see your tests execute. For each step in the testcase, it snapshots the browser so you can go back and look at what the DOM looked like at that step.

Since Cypress isn’t finished yet you cannot really compare it to the other frameworks, but it feels really sophisticated and polished. There are major things left to implement though, for example you can only run tests in Chrome and Electron right now; Firefox, Edge and IE is not available.

Conclusion

It’s amazing that there are so many good tools out there to chose from and so many talented people working on them.

In the end I decided to not use wd.js because it’s not maintained actively enough, same goes from nemo (which also isn’t used enough outside of PayPal). Intern was too difficult to setup and in transition between v3 and v4 and I didn’t really see the value in Chimp over WebdriverIO. I also decided to skip Cypress because it’s not finished and cannot test Firefox etc, and even when v1 is out it will require some time to mature. Also it’s risky that there are so few developers working on it (right now), I prefer tools with broad community participation (no doubt they will try to build such a community).

If I rank the remaining frameworks, I get something like this (best up top):

- webdriver.io

- TestCafe

- NightwatchJS

- CodeceptJS

- selenium-webdriver

There are many things factoring into this ranking; for example on a technical level, NighwatchJS is really good but the community momentum around WebdriverIO seems so much stronger. I’m still pretty interested in seeing what the limitations are of non-selenium E2E testing. Because of this, my plan is to write a slightly larger test suite in both webdriver.io and TestCafe, and have them run in parallel for a while so I can get some more experience of how they work. I will also be checking back with Cypress after they release a stable version that can test Firefox, Edge and IE.

If you have to pick a single test E2E framework today, I recommend webdriver.io.

Epilogue

Did you like this post? Tweet about it or post it on whatever other network / thing you’re on.

Did I miss some important feature / aspect of some framework? Did I miss an entire framework? Tweet at @mo_molsson or drop a comment below. Thanks for reading!

2: The median "Issue Latency" and the fraction of open issues among all issues, are both computed using the excellent service Is it maintained?.